In an age where speed, convenience, and affordability dominate purchasing decisions, choosing the cheapest option often feels like the smartest move. Whether we are buying household items, running a business, or shaping public policy, low prices are usually framed as a success.

Yet, experience repeatedly proves otherwise. The cheapest straw—both literally and symbolically—often ends up being the most expensive choice over time. This idea highlights a crucial distinction many people overlook: the difference between upfront price and true cost. When hidden consequences are ignored, what seems like a saving today can become a significant burden tomorrow.

Plastic straws provide a clear and relatable example. For decades, they were the default option for cafes, restaurants, and fast-food chains around the world. They were incredibly cheap to manufacture, easy to transport, and simple to dispose of.

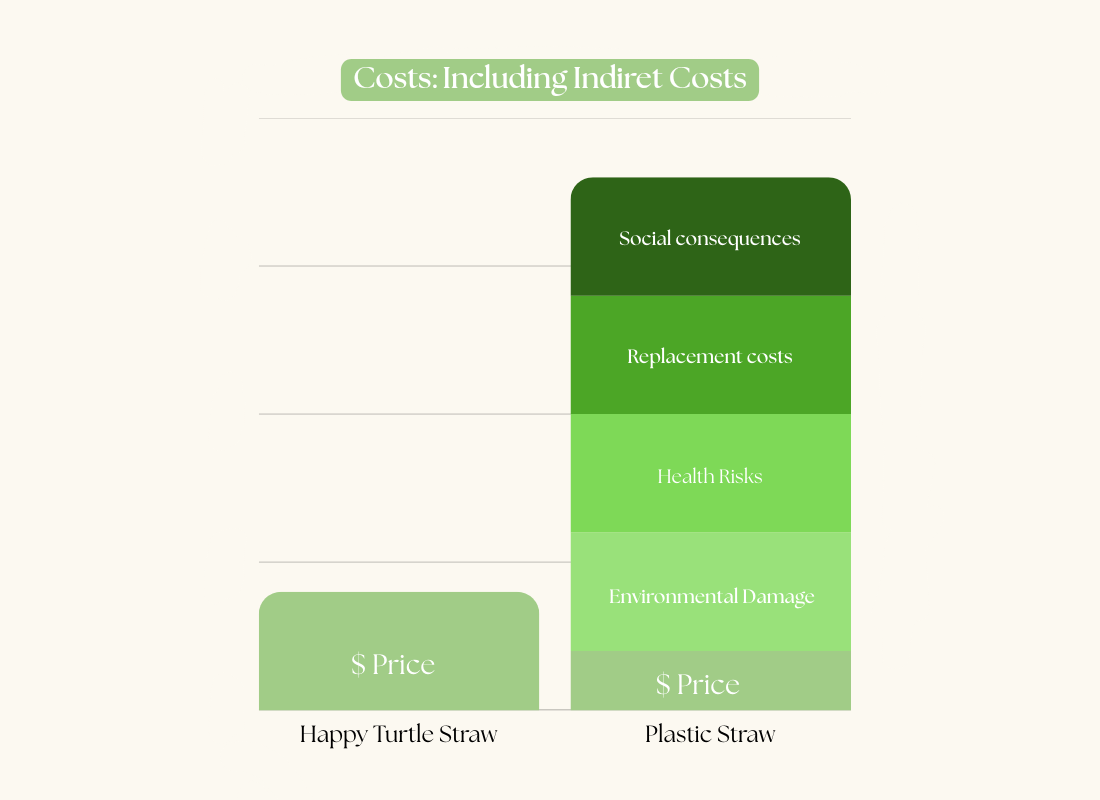

From a narrow financial perspective, they made perfect sense. Alternatives such as metal, glass, silicone, or even paper appeared unnecessarily expensive by comparison. However, this calculation focused only on immediate expenditure, not on the long-term impact of producing, using, and discarding billions of single-use plastic items every year.

One of the largest hidden costs associated with the cheapest straw is environmental damage. Plastic straws are typically used for only a few minutes, yet they can persist in the environment for centuries. When waste management systems fail, or when litter is improperly disposed of, these straws make their way into rivers, oceans, and natural habitats.

Over time, they break down into microplastics that contaminate water, soil, and marine life. Cleaning up this pollution requires enormous financial resources, including government-funded cleanup programs, waste infrastructure upgrades, and conservation efforts. These costs are not paid by the manufacturers or consumers who initially benefited from the low price, but by society as a whole.

Environmental harm also carries economic consequences. Polluted beaches and waterways can damage tourism, fishing industries, and local economies that depend on clean natural resources. When ecosystems are disrupted, the cost is felt through reduced biodiversity, declining fish stocks, and increased vulnerability to climate-related events.

All of this stems, in part, from the widespread use of cheap, disposable products. What once saved a business a few cents per customer can end up costing communities millions in lost revenue and restoration efforts.

Health impacts represent another layer of hidden expense. As plastic straws degrade, they release microplastics and chemical additives into the environment. These particles have been found in drinking water, food sources, and even the human body.

While scientific research is still developing, there is growing concern about the potential long-term health effects, including inflammation, hormonal disruption, and increased risk of chronic illness. Treating these conditions places additional strain on healthcare systems and public budgets. Once again, the low upfront price of the cheapest straw fails to reflect the real cost paid over time.

Durability and performance further illustrate why cheap options are often poor value. Low-cost straws are prone to cracking, bending, or collapsing during use. This leads to frustration and waste, as people often use multiple straws for a single drink.

In contrast, higher-quality straws may cost more initially, but when evaluated on a cost-per-use basis, the supposedly expensive option frequently turns out to be far cheaper in the long run. This same logic applies to countless other products, from clothing and electronics to tools and furniture.

Social costs are another often-overlooked factor. The drive to minimize costs frequently pushes production to regions with weak labor protections and low wages. Workers may face unsafe conditions, long hours, and inadequate compensation so that products can be sold as cheaply as possible elsewhere.

Society ultimately absorbs these costs through increased inequality, reduced social mobility, and greater demand for public assistance programs. While these impacts may feel distant from the original purchase, they are part of the same economic system that rewards cheap prices without accounting for human consequences.

Economists describe these hidden impacts as externalities—costs that are not included in the market price of a product. Because they are invisible at the point of sale, cheap items appear more attractive than they truly are. Governments often step in later with regulations, taxes, or bans to address the damage caused by these externalities.

While such measures are necessary, they can be disruptive and expensive to implement. If the true cost had been considered from the beginning, many of these problems could have been avoided or significantly reduced.

There is also a psychological reason why the cheapest option is so appealing. Humans tend to prioritize immediate rewards over long-term outcomes. Saving money today feels concrete and satisfying, while future costs feel abstract and uncertain.

There is also a psychological reason why the cheapest option is so appealing. Humans tend to prioritize immediate rewards over long-term outcomes. Saving money today feels concrete and satisfying, while future costs feel abstract and uncertain.

This cognitive bias encourages short-term thinking, even when evidence suggests it is not the best approach. Recognizing this tendency is the first step toward making more informed and responsible choices.

Fortunately, attitudes are beginning to shift. Many consumers now consider sustainability, durability, and ethics alongside price. Businesses are adopting tools such as life-cycle assessments and total cost of ownership models to better understand the long-term implications of their decisions.

Fortunately, attitudes are beginning to shift. Many consumers now consider sustainability, durability, and ethics alongside price. Businesses are adopting tools such as life-cycle assessments and total cost of ownership models to better understand the long-term implications of their decisions.

These approaches reveal that investing in quality and sustainability often leads to lower costs, stronger reputations, and greater resilience over time.

Ultimately, the story of the cheapest straw is a powerful reminder that price alone is a poor measure of value. When environmental damage, health risks, social consequences, and replacement costs are taken into account, the cheapest option frequently proves to be the most expensive.

By looking beyond the price tag and considering the full impact of our choices, we can make decisions that are smarter, fairer, and more sustainable. In doing so, we learn that true savings come not from paying the least today, but from paying wisely for the future.